By Bill McEvoy

In honor of National Nurses Week, local historian Bill McEvoy has compiled histories of some of the Civil War nurses who are buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery. This is part one of seven.

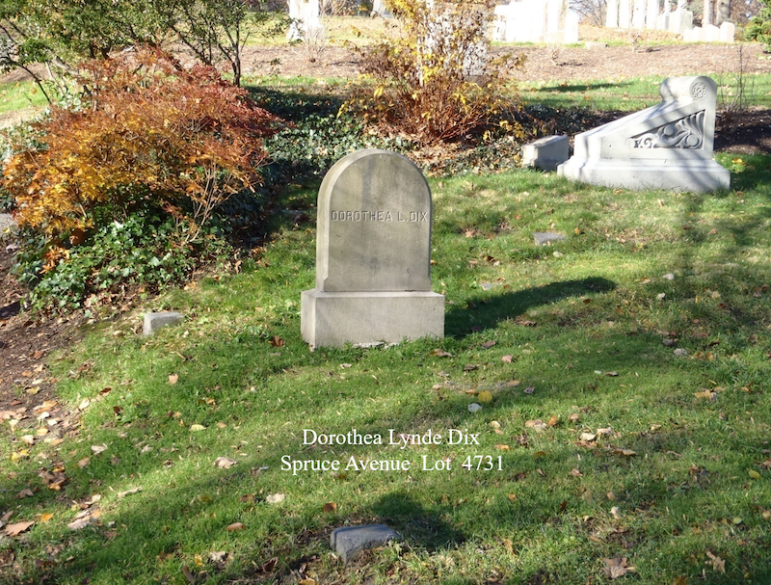

Dorothea Dix was born on April 4, 1802, in Hampton Maine. She died on July 17th, 1887, at the State Asylum in Trenton NJ.

Dorothea had founded that asylum. In 1848 she opened the first state hospital for the mentally ill there. Five years before she died, the State provided her with a home there. Eventually, she opened 32 such hospitals, in 12 states, for the Mentally ill.

Her, father, Joseph was a traveling preacher. He was an alcoholic, religious fanatic, and distributor of religious tracts He died in Boston in 1821 from intemperance.

Her mother had poor mental health.

In 1814, Madame Dorothy Dix, Dorothea’s seventy-year-old paternal grandmother, decided that her son and his wife were no longer capable of caring for their children. Madame Dix took the three children, including Dorothea, to live at the Dix Mansion in Boston. Dorothea’s parents went off to live with relatives. Madame Dix raised Dorothea in the Congregational church. After attending Reverend William Ellery Channing’s service, she became a Unitarian.

Her grandfather, Elijah Dix, was an influential importer of European pharmaceutical products, chemicals, and appliances. He created the family fortune. As an entrepreneur, he developed local merchant institutions and diversified his investments.

The Dix family mansion, built on Orange Street in Boston with its tailored botanical gardens, bespoke of the standards of the aristocratic community. He also transformed State Street into a city enterprise and erected chemical factories in South Boston.

In 1800, her father married Mary Bigelow, who, according to his father, Elijah Dix, was a step backward for the family’s reputation. As Elijah Dix’s prestige and wealth grew, he invested in real estate, purchasing vast acreage in western Maine and developing a commercial center known as Dixmont, Maine. Because Joseph failed to graduate from Harvard, to make a place for himself in Boston, his father provided the couple with land in Hampden, Maine.

Like her mother, Dorothea suffered from depression.

At the age of 12, she went to Worcester MA to live with an aunt. When she was 14, she taught girls her own curriculum in natural science and ethics.

Dorothy wrote several books and articles including, the textbook, Conversations on Common things in 1824. It can be downloaded from Google books without cost.

In 1836, she traveled to Europe, needing a rest after attending to Madame Dix’s illness. Dorothea was also afflicted with tuberculosis. While in Europe she became interested in Prison and Mental Illness Reform.

In 1838, Dorothea returned to Boston. In 1841, she began to teach women at the Cambridge jail. She also ensured that the insane inmates were separated from the criminals. Networking experiences caused her to begin a crusade for prison and mental hospital reform. She toured the United States. In 1845 she published her remarks on prison discipline in the United States.

In 1861, one week after the Civil War began, she volunteered to help. President Lincoln appointed her Superintendent of Union female nurses. Although her health was sometimes poor, she never missed a day from her duties. She served without monetary compensation.

Among her requirements for nurses was that they be plain looking, over 30, and wear black or brown skirts. Bows, curls, jewelry, and hoopskirts were forbidden. Dorothea recruited 3,000 nurses.

Some called her “Dragon Dix” for her perceived dictatorial leadership style. To many, she was controversial and often an unpopular figure.

When wounded soldiers began pouring into the hospitals in Washington, she was shocked by the War Department’s lack of preparation. Because of the shortage of ambulances, Miss. Dix purchased one with her own money and sent it to the battlefield to rescue the wounded soldiers still there. Obviously, more hospitals were necessary.

The immediate solution was to commandeer private homes in Washington, including the Hallowell House on Washington St., the Tibbs House, the Fowle and Johnson homes on Prince St., and the Grosvenor House in Washington. Those were in addition to churches and a theological school. Miss Dix made it a point to visit all of those locations.

As the need for more nurses arose, she relaxed her restrictions on recruits in favor of taking women who were trained nurses, or just willing to help. Experiencing four long years of death and destruction, she wrote to a friend that “This War is breaking my heart.”

Women nurses were employed at the ratio of one to every two soldiers. They received forty cents a day, rations, living quarters, and transportation. Those guidelines were altered later in the war,reducing the wage and increasing the ratio to one nurse to every ten beds, a number later raised to thirty. Women nurses were limited to serving at base hospitals unless they were needed for an emergency elsewhere.

Dorothea traveled to many military hospitals away from the east coast to help organize and conduct inspections. When the St. Louis hospitals were struggling severely, she helped to raise $700,000 for nurses and supplies by appealing to other Union States for financial help.

Not everyone appreciated her efforts, however. Many surgeons, and citizens alike, resented her authority to inspect their hospitals. Although she eventually lost the authority as the sole hiring agent, she continued her volunteer position until the war ended in 1865, and 18 months thereafter.

There are two revealing descriptions of her work during that time. Historian Benson John Lawson described her:

“Like an angel of mercy, she labored day and night for the relief of suffering soldiers. She went from battlefield to battlefield when the carnage was over, and from camp to camp, giving with her own hand comforts to the wounded and soothing the troubled spirits of the dying. The amount of happiness that resulted from the services of this woman can never be estimated.”

Her friend Doctor Caroline Burkhardt said:

“She was a very retiring, sensitive woman, yet brave and bold as a lion to do battle for the right and for justice. She was very unpopular in the war with surgeons, nurses, and any others, who failed to do their whole duty, and they disliked seeing her appear, as she was sure to do if needed …

She was one who found no time to make herself famous with pen and paper, but a hard, earnest worker, living in the most simple manner, often having to be reminded that she needed food…

Every day recalls some of her noble acts of kindness and self-sacrifice to mind. She seemed to me to lead a dual life, one for the outside world, the other for her trusted, tried friends.” – Civil War Medicine, Corrine Coccimiglio, Savannah Dyer, Olivia George, Ariana Montemayor

The writings of the nurses who served under her run the gamut of opinions.

Eight other nurses are presented in this presentation. Emily Parsons, Mary Phinney Von Olnhausen, and Hannah Stevenson mention Miss. Dix. Their following segments will describe the hardships and self-sacrifice they endured caring for the wounded, several at significant risk to their own health.

Dorothea Dix undertook a position that had never existed. There were no guidelines for her to accomplish the herculean job. We shall hear the difficulties that she had with some of her nurses, as well as various male doctors and certain officers that she had contact. She obviously had the full backing of President Lincoln. He was not influenced by critics who used political routes to impede her management.

Much of this narrative was taken from the following:

Meredith Mitchell’s 2011, article, published, by the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority, Biography.com and Barbara Ann Caldwell’s, Dorothea Lynde Dix: Privilege, Passion, and Reform and womenhistoryblog.com.

Find the gravesites of the Civil War Nurses by entering their name here: https://www.remembermyjourney.com/Search/Cemetery/325/Map Bill McEvoy can be reached at billmcev@aol.com

Very much appreciated piece of history- those with mental illness, prisoners, and dying and wounded soldiers saw their destinies changed due to the tireless efforts of this amazing woman. So many facts I didn’t know!