{The following piece was written by State Sen. Will Brownsberger (D – Belmont) who represents Watertown in the Massachusetts State House}

The House and Senate have both now given initial approval to legislation to make it easier to take guns away from people who are a risk of harming themselves or others. It will likely be finalized and enacted before the end of this session.

We already have strong laws that allow a person to seek protection of the court, including removal of firearms, when he or she fears violence from a partner. And school shootings are hard to predict.

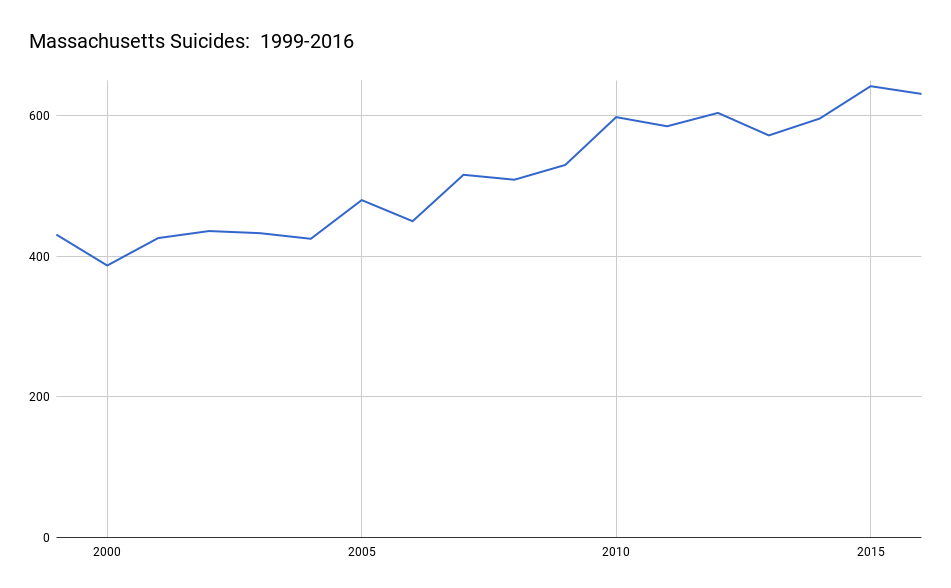

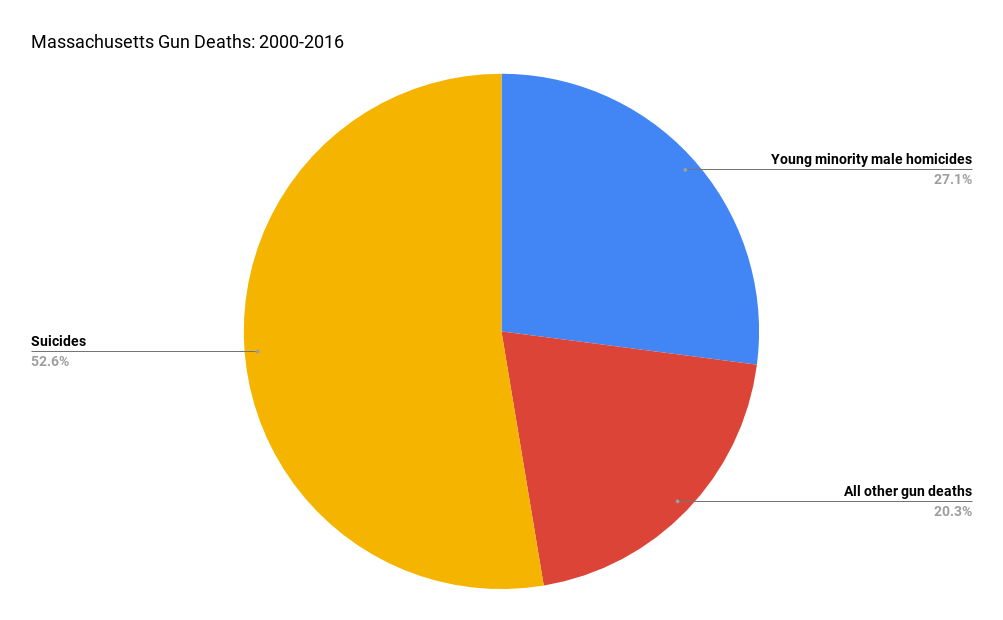

The best argument for the new legislation is that it will reduce the dominant but least visible category of gun death: suicide. Suicide in Massachusetts has risen 35 percent since 1999 — a troubling rise that is mirrored in other states. In Massachusetts, over the 17 years from 2000 through 2016, there were 3,736 deaths due to firearms. Of these, 1,966 or 52 percent were suicides. (Except when otherwise noted, death statistics in this post are computations based on data extracted from the CDC website on June 8, 2018.)

Under the legislation, if relatives or certain others become aware of severe depression and suicidal thoughts on the part of a gun owner, they will be able to go to court to urge a judge to remove the weapons. Police authority arguably exists to remove weapons in these circumstances, but the new legislation gives some procedural clarity. It will be especially helpful when there is a need to act swiftly.

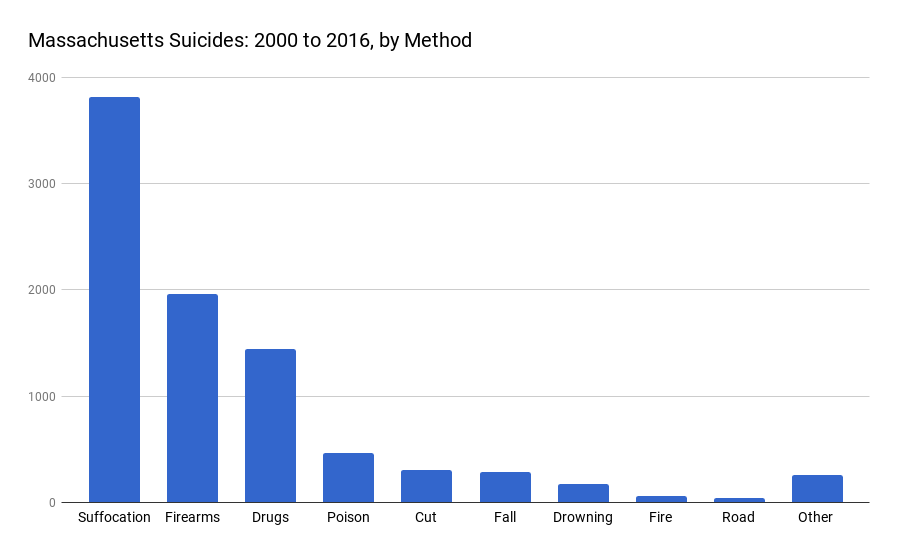

If people, at their most desperate moment, use a gun to attempt suicide, the chances are that they will succeed. In one study in the Northeast, 91 percent of suicide attempts by gun were successful. The other easy way to attempt suicide — self-poisoning with drugs — is much less effective: In the same study, poisoning accounted for 74 percent of the attempts, but only 14 percent of the fatalities. (Suicides by hanging/suffocation are more common than firearm deaths in Massachusetts and are all too successful, but they are hard to control.)

While people who fail at suicide are at relatively high risk to make another attempt, one meta-analysis found that only 18 percent re-attempted within one year and that after nine years, only 7 percent had died by suicide. Preventing the impulsive trigger-pull may give someone a new long-term lease on life.

As compared to other states, Massachusetts has a relatively low rate of household gun ownership and a correspondingly low rate of suicide by gun, but firearms do account for 22 percent of successful suicides in Massachusetts (1,966 of 8,820 suicides from 2000 to 2016).

Firearm suicide is especially a problem among older white males. In Massachusetts, firearm suicide is 13 times more common among males than among females and two times more common among whites than among blacks. The risk rises with age.

The other major category of gun death, also all too often relegated to a back page of the papers, is gun violence among young minority males. Death by shooting is eight times more common among males than females and 10 times more common among blacks than among whites. Risk is highest for people in their 20s. Although they are a small fraction of the population, black and Hispanic males aged 15 to 35 accounted for 59 percent of all the firearms homicides in the state from 2000 through 2016 (1,011 of the 1,714 intentional gun homicides). The risk of gun death among black males 20-24 is 25 times higher than the risk of gun death for non-Hispanic white males in the same age bracket.

Our recent legislation will do nothing to reduce the problem of urban gun violence. That’s a larger problem to which we devote significant resources — education, summer jobs, gang outreach, law enforcement, corrections. Doing more to bring young people back on track has to remain one of our central concerns.

The legislation we approved this week will help save some lives among those in distress.

Highlights of the Legislation

What is the basic idea?

Allow a court to issue an Extreme Risk Protection Order (ERPO) order to take firearms from a person who has become dangerous.

Which courts can issue an ERPO?

Local district courts.

Who can seek an ERPO?

Family members and household members (defined broadly but specifically) and local licensing authorities.

When will the court issue an ERPO?

To prevent bodily harm. A court will issue an ERPO if it finds “that [a person] poses a risk of causing bodily injury to self or others by having” a gun.

What evidence does the court need to issue an ERPO?

It needs to find risk of bodily injury by a “preponderance of the evidence.”

Does the person with the firearms get to respond?

Yes. In general, notice of a petition for an ERPO must be made seven days prior to a hearing on the petition.

What happens if the ERPO is issued?

The person’s gun license is suspended and they must surrender their guns.

Can a person get their guns back?

Yes, when the ERPO expires or is revoked, provide the person is found to remain suitable for licensing.

What happens in emergency situations?

A court may issue an emergency ERPO without hearing if the court finds “reasonable cause to conclude that the respondent poses a risk of causing bodily injury to self or others by being in possession of” guns. Emergency orders may be executed immediately, but can be lifted after a prompt hearing.

What about abuse of ERPO petitions?

Any person who files a false petition or files a petition with intent to harass can be imprisoned.

What about liability for failing to file a petition for an ERPO?

The law expressly disclaims any duty to file an ERPO petition and provides that no family or household member can be found liable for failure to petition.

Does the act specifically address mental health issues?

Only in the following respect: when an ERPO is served on a person, they should be provided information about mental health resources. Arguably, this is a minimal response: 58 percent of suicide victims have a current mental health problem. Of course, ERPOs are not limited to suicide situations and much violence is not related to mental health problems.

What else does the act do?

It replaces our current ban on stun guns, which was found unconstitutional, with a requirement that people be over 21 and have an FID card (lower tier gun license) to purchase a stun gun.

Resources

- Overview of Massachusetts Gun Laws

- The Truth about Suicide and Guns, Brady Center

- Fatal Injury Reports, Center for Disease Control

- Debate about Extreme Risk Protective Orders on this site

Thank you for the clear explanation and for your leadership on the Judiciary Committee, Senator Brownsberger. And thank you to Editor, Charlie Breitrose, for including it in the Watertown News. It is already a positive that our local Police Chiefs sign off on gun licenses in Massachusetts. These new bills help create a judicial procedure when danger is at hand. I hope the final contains all the important sections and that Governor Baker signs it into an effective law.