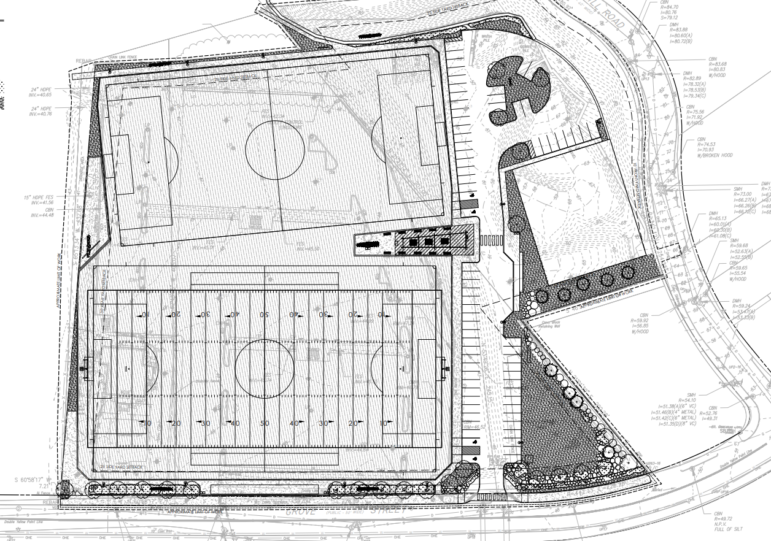

BB&N A planning document showing the design for the athletic field to be built by Buckingham, Browne & Nichols School on Grove Street. The project has met resistance from residents who oppose using artificial turf on the fields.

After receiving many letters and comments opposing the installation of artificial turf at a new athletic complex being proposed by Buckingham Browne & Nichols School, the Planning Board grudgingly approved the project. The decision was made with strong objections by members of the board and after efforts to delay the vote proved unsuccessful.

The project would build two athletic fields on property at 165 Grove Street, just north of Filippello Park.

In November 2020, BB&N and the Town of Watertown have entered into a memorandum of understanding (MOU) where the school would have use of the fields at Filippello Park after school and during a few weeks in the summer and spring. Watertown residents would be able to use the BB&N fields in the evenings and weekends.

The school also has plans in the future to build a field house on the site. The property is also the site of the historic Shick House, and in February the Watertown Historical Commission approved a 12 month demolition delay on the house to give time to find a way to preserve the home.

At the June 9 meeting, Planning Board member Janet Buck proposed that the project be taken up at a future meeting. She cited the fact that a petition signed by 229 Watertown residents had been given to Town Council President Mark Sideris in May asking that the artificial turf be replaced by natural turf due to health and safety concerns, such as the increased heat on turf on hot days and hazards from chemicals from the artificial grass and fill material. The signatures have not been verified yet, Buck said, due to the Town Clerk vacancy. The Watertown Environment & Energy Efficiency Committee also sent a letter opposing the use of artificial turf.

School officials said that artificial turf was selected because natural turf would not stand up to the amount of use of the fields by the school and town residents.

Buck said: “It would be prudent for this board to continue the case to a later date so a petition submitted to the Town Council requesting the Council schedule a public hearing regarding the issues surrounding the Council’s passage of the Memorandum of Understanding.”

She added that residents have also requested that a second community meeting be held.

“We can all agree a huge number of comments have been received from residents,” Buck said. “The first community meeting did not offer much of any dialogue, and I observe the materials submitted afterward were very slanted to downplay the comments offered by the community.”

The Town is limited by what it can demand from BB&N, said Assistant Town Manager Steve Magoon, who is also director of the Department of Community Development and Planning. The project falls under the Dover Amendment in Massachusetts’ zoning laws, which he said prevents the Planning Board from denying approval of the project due to the artificial turf.

Attorney Amy Kwesell, who served as the Town’s attorney for the case, said that the Dover Amendment prevents any local zoning ordinance or bylaw from restricting or regulating any land or structure used for educational purposes by a non-profit educational organization. Some areas can be regulated by local Planning and Zoning Boards, Kwesell said, including building height and bulk, yard size, lot area, setbacks, ratio of open space, parking and building coverage.

Magoon added that he did not think that a second community meeting would be possible because that is part of the process at the start of a Planning Board case, and BB&N has now submitted a final proposal to be considered by the Planning Board.

The Planning Board heard more than an hour of comments from residents.

“It is interesting to sit here for almost two hours and hear so many negative comments about artificial turf,” said Planning Board Chair Jeffrey Brown. “But, the approval is about the plan, as opposed to the material.”

Planning Board member Payson Whitney said that the decision would be a different one if it was a commercial entity making the application, not an educational one.

“I do not defer to them, but we are bound by the rules we have, and we have Zoning regulations and the Dover Amendment in this case, ” Whitney said. “It is not for our board to legislate either one.”

BB&N

The Town of Watertown and Buckingham Browne & Nichols School (BB&N) agreed to a field sharing plan where the school would get some use of Filippello Park, while the Town could use new athletic fields to be built by BB&N on Grove Street.

Planning Board member Jason Cohen asked if the board could delay the vote and wait until unresolved issues, such as the artificial turf and the Council’s hearing on the MOU can take place. He noted that construction cannot begin immediately because of the Historical Commission’s demolition delay.

Magoon said the issue of the artificial turf and the MOU do not fall under the Planning Board’s purview, and should not be considered by them when making the decision. He added that they cannot be used as reasons for denying approval due to the Dover Amendment.

“Our attorney from KP Law has provided legal counsel to us as a Town, and I suggest I think it would be very serious going against the recommendation of our own legal counsel,” Magoon said. “There is serious peril there.”

Bill York, attorney representing BB&N on the case, said that he did not think that the Planning Board could use the artificial turf or the MOU as a reason to delay approval.

“A motion for reconsideration that is before the Council has nothing to do with that,” York said. “The surface of the field is probably not going to change. (A delay) could change the Town’s ability to use the field. We hope that doesn’t happen. BB&N is moving forward with the design that is there.”

Whitney made a motion to approve the site plan review with the conditions added from Town’s planning staff. At first no one seconded the motion. Cohen asked if getting no second to the motion would be the same as denying the proposal.

Kwesell said yes, adding that the board could not deny the proposal: “It is a site plan for an approved use, which cannot be denied; and second, it is under the Dover Amendment so it cannot be denied.”

Cohen asked what would happen if the Planning Board did deny the approval, asking if the case would be taken to Land Court for a ruling.

“I could not confirm that, Attorney York would have to confirm that,” Kwesell said. “That would be my assumption — with all the time and energy they have spent on this — that’s what they would do.”

If Watertown lost the Land Court Case, Kwesell said, they would lose the right to require conditions.

After the legal explanation, Brown said: “It is very odd to be in a situation where you have to vote a certain way. I am not happy with that situation but we will see what happens.”

In the end, the BB&N fields proposal was approved 3-1 by the Planning Board, with Buck voting “no” after the majority had already been reached.

Municipal officials involved in local zoning and land use planning should keep in mind the provisions of a Massachusetts statute commonly known as the Dover Amendment. M.G.L. c. 40A, § 3. Originally adopted in 1950, the statute mandates that proposed religious and educational land uses be given more favorable treatment than other proposed uses (such as

residential, commercial or industrial) under local zoning ordinances and by-laws. The failure of a city or town to accord such favorable treatment may lead to protracted (and expensive) litigation and, in some cases, allegations of unlawful

discrimination.

If an owner or developer believes its project is entitled to Dover Amendment protection, its first step is to make a two-part showing to the local building inspector. First, the applicant must demonstrate that the proposed use of the property is for “religious” or “educational” purposes. When it comes to houses of worship or classrooms, this showing will be relatively

straightforward. When it comes to a parking garage or half-way house, however, the purpose of the proposed use may not be so easily discerned. In less obvious cases, the building inspector may wish to consult with municipal counsel.

Second, the applicant must demonstrate that the proposed use of the property for “religious” or “educational” purposes is not a mere ancillary use but, rather, the dominant or primary one. Again, such a showing may not be immediately evident in all cases.

If the building inspector determines (either with or without legal input) that the applicant has satisfied the requisite two-part showing, then the Dover Amendment applies, and the only zoning ordinances or by-laws that a city or town may enforce

against the proposed project are reasonable regulations regarding the bulk and height of structures, yard size, lot area, setbacks, open space, parking and building coverage requirements. Other zoning regulations regarding, for example, density, screening, traffic and signage, are not enforceable as against a Dover-protected project.

In addition, any regulation of the bulk and height of structures, yard size, lot area, etc. (i.e., the permissible subjects for regulating protected uses) must be “reasonable.” What a court considers reasonable will depend on the facts in each particular case. While practical nullification of a proposed religious or educational use will likely fail, cities and towns may

still apply requirements that are related to legitimate municipal concerns and which bear a rational relationship to those concerns. Notably, the burden will be on the applicant to prove that the regulation of its proposed religious or educational use is unreasonable.

If the building inspector determines that a proposed use is not protected under the Dover Amendment, the applicant may appeal this decision to the local zoning board of appeals within 30 days. M.G.L. c. 40A, §§ 8 & 15. If the ZBA affirms the decision of the building inspector, the applicant may take a further appeal by filing an action in the Land Court, Superior Court or Housing Court within 20 days. M.G.L. c. 40A, § 17.

Finally, while the Dover Amendment represents a firm thumb-on-the-scale for protected uses, it does not apply to non-zoning regulations concerning public health, safety or the environment, such as Board of Health regulations, the State Building Code, the State Plumbing Code, or state or local wetlands protections. Such regulations are still enforceable

regardless of an applicant’s proposed religious or educational use.

Good for them. This will be great for the residents of Watertown for years to come.

Thanks for a very thorough and accurate summary, Charlie.