Charlie Breitrose Historical Society of Watertown member Bob Bloomberg glances at the new historic marker near the former location of the Shick House. The marker was dedicated on June 26.

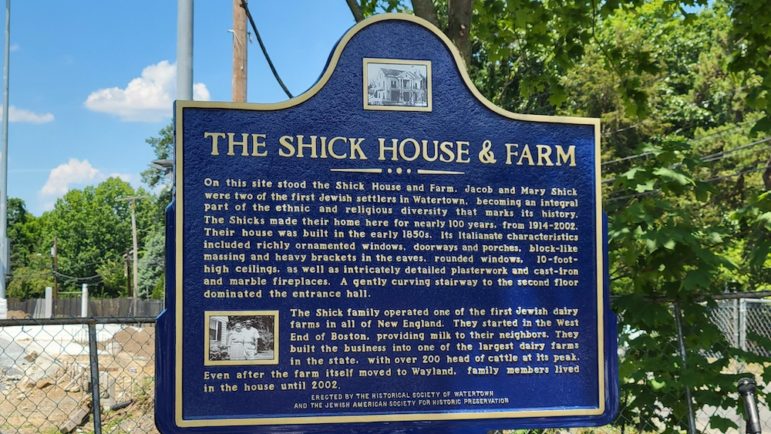

A shiny, new blue sign with gold lettering now sits feet away from where a farmhouse stood for about 170 years. The historical marker is the only reminder of the home owned by the family that ran the first Jewish-owned dairy in Massachusetts and of Watertown’s rich agricultural history.

The Historical Society of Watertown unveiled the new marker for the Shick House on Sunday afternoon. The home that was located at 183 Grove St. in East Watertown stood on land that is being turned into athletic fields. The marker was erected near the entrance to the City-owned Filippello Park.

Marilynne Roach, president of the Historical Society of Watertown’s executive board, thanked the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation, which covered the entire cost of the Shick House historical marker. “Let’s hear it for them,” she said.

“It’s hard to think of Watertown as agricultural now, except for the occasional Victory garden,” Roach said. “It has been with the three sisters — corn, bean and squash — since forever. There was a time when Watertown was cattle country, had subsistence farms, market gardens, and commercial green houses, which lasted into the 20th century.”

Council Vice President Vincent Vincent Piccirilli attended the unveiling of the sign for the Shick House.

“Unfortunately, it is no longer here, despite various efforts to preserve it. The best we can do is remember the house here and remember it’s very unusual, even 100 years ago, to have a Jewish dairy here in Watertown,” Piccirilli said. “It speaks to the welcoming environment in this community of immigrants that I think Watertown has always had. A little bit of history that will be remembered by this plaque.”

Steve Owens

The Shick House was demolished in early 2022. The Italianate style house had stood there since the 1850s.

Jacob Shick immigrated to Boston’s West End in 1905, and brought his wife Mary and two daughters over four years later, said Bob Bloomberg, a member of the Historical Society who researched the Shick family and spearheaded the effort to get a historical marker. Bloomberg’s research started when he was looking for a project that intertwined his interest in Watertown history and Jewish history. He found a personal connection, too, because his grandmother had lived on the same street on which the Shicks lived, and his great-grandfather was a bottler.

“It was intriguing to me to think that he might have worked for the Shicks,” Bloomberg said.

Jacob’s cousin had started a milk route in the West End. Jacob bought cows in Brighton and stabled them in Watertown.

“He built the business one customer at a time while still keeping his full-time job as a coppersmith,” Bloomberg said. “Mary was the business manager.”

The farm started in 1914 on California Street, where the Shicks lived in what Bloomberg described as a shack with no stove, no indoor plumbing, and no electricity. After receiving complaints from neighbors, and a notice to vacate from the Watertown Board of Health, the farm moved to Grove Street in 1915.

The house itself also stood out as an example of an architectural style that is hard to find. It was built in the 1850s and had been used as a farmhouse.

“It was an outstanding example of the Italianate style of architecture,” Bloomberg said. “(Some) of its major characteristics were its richly ornamented windows, doorways, and porches. The interior had detailed plaster work, fireplaces with marble tops, and a cast iron stove in one of the front rooms. A beautifully curving wooden banister led up to the second floor.”

BB&N

Interior shots of the Shick House, showing the stairway and stained glass around the doorway.

The Shick House not only served as home to the family that owned the farm, it also housed workers, and at times friends from Boston’s West End, who would summer there.

The family had five acres of land, and stabled 25 cows that grazed on Mount Auburn Cemetery land and along the shores of the Charles River, Bloomberg said. The business expanded as their customers moved from the West End to Dorchester and Roxbury. In 1937, needing a brandname to compete with the likes of Hood and other dairies, the business was incorporated as The Watertown Dairy.

“By the mid 1930s, the Shick property was too small to accommodate a major dairy farm. The Shicks purchased an estate with 250 acres of land in Wayland,” Bloomberg said. “They now had about 250 cows which produced 4 tons of milk a day. They wholesaled milk to grocery stores and smaller dairies. It wasn’t just a dairy farm. By 1950 it had become the largest grower of sweet corn in New England. That was the peak.”

Jacob died in 1950, and then Mary semi-retired. Only one son, Hyman, stayed in farming. The rest of their children and grandchildren went into different occupations.

“Over expansion was probably another contributing factor to the decline of the business, which dissolved in 1982,” Bloomberg said. “Even after the farm left Watertown family members continued to live in the Shick house until 2002.”

Bloomberg thanked Larry Shick, a grandson of Jacob and Mary, who provided him with many stories and photos of family members and their house. Larry, who is now in his 80s, lives in Florida and was not able to attend the ceremony.

Piccirilli thanked the Historical Society for creating the remembrance to a piece of Watertown’s history. He recalled what the area looked like when he moved to town 35 years ago.

“I was very excited to find a junkyard half a mile from my house to buy parts for my old car,” Piccirilli said. “It was sandwiched between where (the sign stands) — where the incinerator was — and on the other side of it was the dump for Mount Auburn Cemetery.

“Even then the house was slowly decaying.”

When the land was going to be sold from the Mount Auburn Cemetery to Buckingham Browne & Nichols School (BB&N) it became clear that the house would be torn down unless a new spot could be found. A one-year demolition delay was approved by the Watertown Historical Commission in February 2021. The Historical Society started efforts to save the house, Bloomberg said.

Charlie Breitrose

More than a dozen people attended the dedication of the Shick House historical marker Sunday, despite temperatures in the 90s.

The house was already on the Massachusetts Cultural Resource Information System database, and the Historical Society worked to get it on the National Park Service’s Historic American Building Survey, Bloomberg said. Photos of the interior and exterior of the home will soon be on the Library of Congress website, he added.

The preservation effort ultimately proved too difficult and pricey.

“We were faced with two insurmountable obstacles. The house had been neglected for 20 years. It was in a state of terrible disrepair,” Bloomberg said. “Our second problem was finding a site in Watertown which could accommodate a very large building. We estimated that the cost of moving a house, restoring it and renovating it, remediating the mold and mildew problem, and then maintaining it would be about $2 million.

“That was clearly unobtainable even if there was a place in Watertown to move it, which there wasn’t.”

The Shick House was demolished in early 2022, and the site is in the midst of being turned into athletic fields. On Sunday, an expanse of small grey stones could be seen, which will serve as the base of the artificial turf.

Charlie Breitrose

The Shick House historical marker was paid for by the Jewish American Society for Historical Preservation.