By Bill McEvoy

In honor of National Nurses Week, local historian Bill McEvoy has compiled histories of some of the Civil War nurses who are buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery. This is part four of seven.

If you heard this name recently, it stemmed from PBS’s series, Mercy Street. I located and read her diary in 2012, long before PBS’s 2016 series. I gave several lectures that noted her diary. Perhaps someone then read the book and brought her story to the public. If you saw the series and read her diary, the contrast between facts to fiction is shocking.

Much of the following, in italics, was taken from Mary Phinney von Olnhausen’s diary. After Mary’s death, her nephew, James Phinney Munroe published the diary, Adventures of An Army Nurse in Two Wars, Little, Brown Company 1903.

Mary died, from paralysis, in Lexington, Massachusetts, on April 12th, 1902. Her grandfather was Doctor Josiah Bartlett from Charlestown. At age 16 he was at the Battle of Bunker Hill. He was the Surgeon’s Mate to Dr. John Warren. Josiah was later made a full Surgeon and served through the rest of the war.

In 1849 upon the death of her father, the Lexington farm was sold. Those daughters who were not married were left to their own resources. Mary went to Manchester, New Hampshire, and became a designer of print goods. That was a new career for women.

On May 1st, 1858, she married, Baron Gustav A. von Olnhausen. Gustav was 49. Mary was 39. Reverend Theodore Parker, Transcendentalist, Abolitionist, and Member of the Secret Six, performed the wedding. The Secret Six. That a group of men secretly funded the 1859 raid on Harper’s Ferry by abolitionist John Brown.

Their marriage record notes that it was the first marriage for each. Barron von Olnhausen left Saxony after 1848 due to unrest and financial troubles. That led to the selling of his castle. When they met, he was making a meager living as a chemist at a dye house in the Manchester Mills, located in New Hampshire.

He died Sept. 13, 1860, of kidney disease and is buried with Mary. Two months after her husband’s death, Mary moved to Illinois to assist her brother’s family; four children and an invalid wife. He was a farmer, and his land was besieged with misery.

Upon learning about the Battle of Bull Run, Mary decided to enter the war as a nurse. When she arrived in Boston, she immediately appealed to Dorothea Dix.

Mary was promised to be placed at once. The delay was so long that Mary began to doubt her, however, she was summonsed to Washington. She received the news in August of 1862. It was on a Saturday, and she left Monday. Mary was assigned to the Mansion House Hospital, the city’s largest military hospital.

In Mary’s own words:

Miss Dix, who had been appointed by the President head of the army nurses, took me from Washington to Alexandria to the Mansion House Hospital.

She told me on the journey that the surgeon in charge was determined to give her no foothold in any hospital where he reigned, and that I was to take no notice of anything that might occur and was to make no complaint whatever might happen. She was a stern woman of few words.

There seemed to be much confusion about the Mansion House which before the war was a famous hotel and every part of it was crowded.

She left me in the office and went in search of Dr. S. The sight of the wounded continuously carried through on stretchers or led in as they arrived from the boats that lay at the foot of the street on which the hospital stood (this was just after that awful Cedar Mountain battle on August 9th). It seemed more than I could bear, and I thought Miss Dix would never come.

At last, she appeared, with Dr. S., who eyed me keenly and, it seemed to me, very savagely, and gave me in charge of an orderly to show me to the surgical ward, as it was called.

It consisted of many small rooms, with a broad corridor, every room so full of cots that it was only barely possible to pass between them. Such a sorrowful sight; the men had just been taken off the battlefield, and some of them had been lying there for four days almost without clothing, their wounds never dressed, so dirty and wretched.

Someone gave me my charges as to what I was to do; it seemed such a hopeless task to do anything to help them that I wanted to throw myself down and give it up. Miss Dix left me, and soon the doctors came and ordered me to follow them while they examined and dressed the wounds. They seemed to me then, and afterwards I found they were, the most brutal men I ever saw. They were both volunteers.

So, I began my work, I might say night and day. The surgeon told me he had no room for me, and a nurse told me he said he would make the house so hot for me I would not stay long.

When I told Miss Dix I could not remain without a room to sleep in, she, knowing the plan of driving me out, said, my child; (Mary was as nearly as old as herself), you will stay where I have placed you.

In the meantime, McClellan s army was being landed below us from the Peninsula.

Night and day the rumbling of heavy cannon, the marching of soldiers, the groaning of the sick and wounded were constantly heard; and yet in all that time I never once looked from the windows, I was so busy with the men.

One of the rooms of the ward was the operating room, and the passing in and out of those who were to be operated upon, and the coming and going of surgeons added so much to the general confusion. I doubt if at any time during the war, there was ever such confusion as at this time.

The insufficient help, the unskillful surgeons, and a general want of organization were very distressing; but I was too busy then and too tired for want of proper sleep to half realize it.

Though I slept at the bedsides of the men or in a corner of the rooms, I was afraid to complain lest I be discharged. I was horribly ignorant, of course, and could only try to make the men comfortable; but the staff doctors were very friendly and occasionally helped me, and someone occasionally showed me about bandaging, so by degrees I began to do better.

The worst doctor had been discharged, much to my joy, but the other one, despite his drinking habits, stayed on. After the morning visit it was no use calling upon him for anything, and I had to rely on the officer of the day if I needed help. I know now that many a life could have been saved if there had been a competent surgeon in the ward.

At this time the ward was full of very sick men and sometimes two would be dying at the same time, and both begging me to stay with them, so I got little sleep or rest. Moreover, I had no room of my own. Occasionally a nurse would extend the hospitality of the floor in hers, and I would have a straw bed dragged in on which to get a few hours’ sleep. This, with hurried bath and fresh clothes, was my only rest for weeks. It was no use to complain.

The surgeon simply stormed at me and said there was no room; while Miss Dix would say, you can bear it awhile, my child; I have placed you here and you must stay; I was at that time her only nurse in the Mansion House.

(End of Mary’s own words)

Later Miss Dix succeeded in getting rid of all the others and replacing them with her own. Mary was renowned for her wound care and high survival rate.

Mary later worked at a military hospital in New Bern, North Carolina where she contracted yellow fever.

It also notes her service in the Franco-Prussian war. As a Baroness, she wanted to tend to her husband’s homeland. Mary and Clara Barton served in American Civil and the Franco-Prussian Wars. They were both awarded the Cross of Merit for Women and Girls, by Kaiser Wilhelm I. That was akin to the Iron Cross.

Upon her return from Europe, In January 1874, she was the Superintendent of Nurses training at the Massachusetts General Hospital. After 10 months it was determined that it was not a good fit for her. The hospital noted her shortcomings as an administrator.

Mary also served two years as the Administrator of the Maternity Asylum at Staten Island, New York.

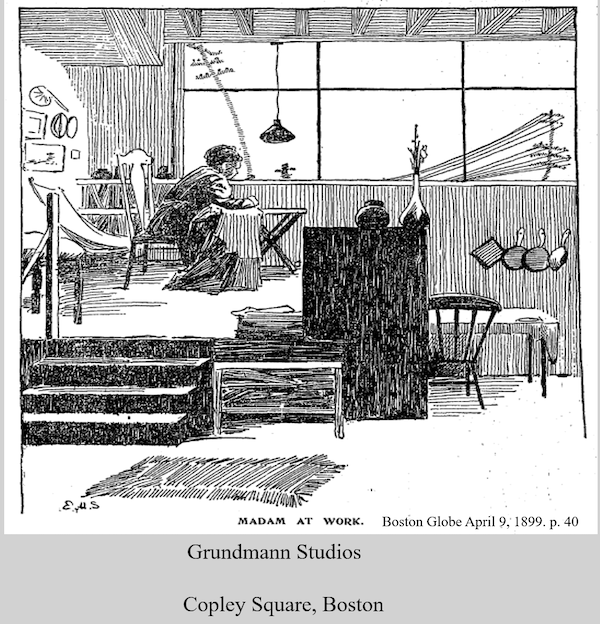

Later Mary lived in a room at the Grundman Studios in Boston. The building was near the Trinity Church in Copley Square. The building later became the home of the Copley Society.

Find the gravesites of the Civil War Nurses by entering their name here: https://www.remembermyjourney.com/Search/Cemetery/325/Map Bill McEvoy can be reached at billmcev@aol.com

Love these histories that show the selflessness of the nurses during the Civil War. Shows the value of a diary which gives a personal touch. Thanks for this series.