By Bill McEvoy

In honor of National Nurses Week, local historian Bill McEvoy has compiled histories of some of the Civil War nurses who are buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery. This is part seven of seven.

Annie Frances Kendall Freitag:

Annie Frances Kendall Freitag was born in Boston on May 4, 1830. She was the daughter of Abel and Anne Mayo Richards Kendall.

In 1856, Abel committed suicide, by hanging himself, in the attic of their Somerset Street home in Boston. His death notice stated that he was depressed and was losing his hearing. A Merchant, he left his family in affluent circumstances.

On June 7th, 1865, she married Frederick Daniel Freitag. His occupation was listed as, Officer, United States Army. He was born in Germany. Frederick’s age was listed as 25 and Annie’s was 35. They had a son, Frederick E., in Boston, on Aug. 25, 1866. He died 2 days later from convulsions.

Their only other child, Joseph Kendall Freitag, was born on Sept. 12, 1868, in New York.

I located the following, written by Civil War Author, and Historian, Ronald S. Coddington. It is from one of his books, Faces of Civil War Nurses Johns Hopkins University Press, 2020. I highly recommend his books.

It is a rare event when a reference to the mental health of a Civil War soldier turns up in primary sources. Today, I found one in the pension file of Annie Francis Kendall Freitag … The soldier to whom she described as suffering from a “distressing nervous condition” was her husband, Frederick Daniel Freitag.

Fred’s military service was notable for his three wounds. The first, at White Oak Swamp during the 1862 Peninsula Campaign, caused a bullet to be forever lodged in his thigh and imprisonment in Richmond for a month.

His other two wounds happened weeks apart during the 1864 Overland Campaign—a gunshot in the hand and a shell fragment in the foot.

Fred managed to recover from all this and mustered out with his comrades in the 30th Pennsylvania Infantry in the summer of 1864. he went on to become an officer in the 24th U.S. Colored Infantry and married Annie in June 1865. Annie, who had served as a nurse and first met Fred as he recuperated from his White Oak Swamp wounding at a U.S. military hospital in Chester, Pa.

They, marveled at his physical strength, in light of his injuries.

Everything changed in 1886 after Fred suffered a breakdown. A physician diagnosed him with consumption and suffering from what Annie noted was a “distressing nervous condition”—perhaps post-traumatic stress disorder.

She attributed his health issues to his war wounds and added, “he passed away after two years of extreme suffering, and utter dependence and disability.” Fred was 48 years old.

I located Fredericks’s grave at the Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, New York.

I added a memorial to Findagrave.com and requested a picture of his marker. They shall place a flag on his grave on Memorial Day.

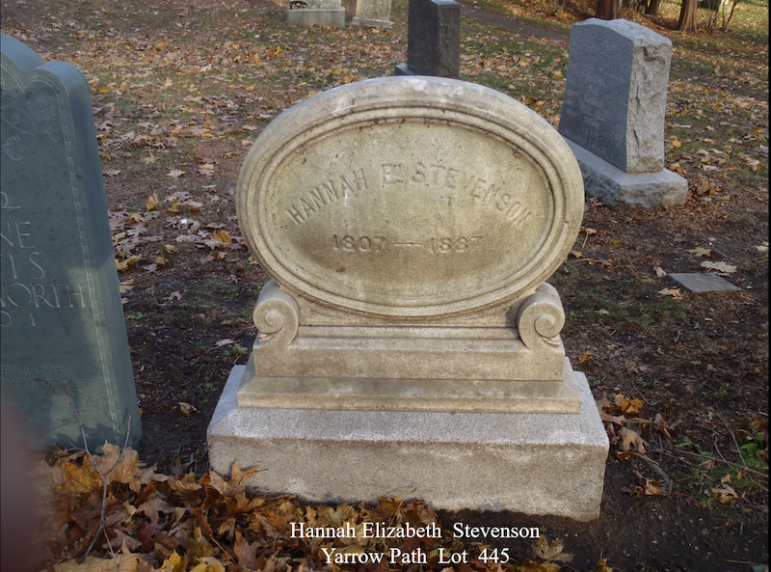

Hannah Elizabeth Stevenson

She was an activist and well-known, Boston abolitionist. In August 1861, she was the first Massachusetts woman to volunteer to serve as a Civil War nurse. Hannah already had a lifetime of service experience behind her.

In the years before she joined the war effort, she had worked for 30 years at the Home for Destitute Children.

Hannah was 53 years old when she volunteered to serve as a nurse. She would serve at multiple Union hospitals between 1861 and 1863.

During the early months of the Civil War, she wrote to her family about her work as a nurse at Columbia College Hospital in Washington.

Hannah lamented the hazards many of the soldiers encountered in the hospitals, including disease, mistreatment by superiors, hunger, and homesickness all the while celebrating the soldiers’ dedication to the Union cause and the endless work of her fellow nurses “whose muscles never surrender” to the demands of the work.

Like most of the more than 20,000 women who served as nurses during the war, Hannah had no formal medical training. As she illustrated in a letter, her male counterparts were often no better qualified, as the male nurses were usually convalescent soldiers unable to return to their regiments.

Hannah’s letters highlighted the difficult relationship between male military surgeons and female nurses. Many male surgeons resented the presence of civilian women in military hospitals.

In June 1861 the federal government named Boston’s Dorothea Dix Superintendent of Female Nurses in hopes that “Miss Dix” (as Hannah refers to her) could ease tensions between nurses and the hospital’s surgeons. She could not.

Many of her letters were critical of Dorothea Dix’s abilities as a manager.

Hannah’s letters also illustrated the awkwardness of serving under the Medical Staff.

One letter stated, “I cannot get over the surprise of being ordered about by these surgeons as they order the privates; they recognize nothing of the peculiarity of the position.”

According to family legend, Hannah was well-known for composing impressive love letters on behalf of young soldiers.

An observer recalled, “all who could limp up to hear the reading, applauding it with merry shouts of laughter, and only wished Miss Stevenson would write their love letters for them, she said it all so much better than they could.”

At the close of the war in 1865, Hannah traveled to Richmond on behalf of the Freedmen’s Bureau, helping to establish schools for former slaves.

Her work assisted this new government agency in enrolling 90,000 former slaves in public schools by the end of the year.

Civil War nurse, Louisa May Alcott dedicated her memoir, “Hospital Sketches” to her, as she was her mentor. That free 106-page book can be downloaded from Google Books.

The Boston Globe July 15, 1887, p. 1 noted her passing.

Miss Hannah Stevenson of Boston, who died last week, was especially noticeable for her charities among the colored people of the Hub.

She was a warm friend and a liberal patron of the Boston Home of Aged Colored Women.

She bore the name of an abolitionist when it cost so much to be one.

Gentle, mild, yet outspoken and positive in her denunciation of wrong, she was one that small but noble band of Christian women who, in the early days, warmly championed the cause of the slave.

Mary McKinnon Tate

She was one of a few married nurses. She died, from diphtheria, on Jan. 29, 1863, at the Douglas Army Hospital in Washington, D.C. Mary was one of a few nurses that died on active duty. She is buried beside her husband James who, within the year, died from lung fever, contracted while serving in Louisiana.

Mary enlisted after James and his brother and nephew enlisted. She followed her husband to the War.

Find the gravesites of the Civil War Nurses by entering their name here: https://www.remembermyjourney.com/Search/Cemetery/325/Map Bill McEvoy can be reached at billmcev@aol.com