The following story is part of a series on local history provided by the Historical Society of Watertown. It was written by David J. Russo, for the October 2012 Historical Society newsletter, “The Town Crier.” At the time, David was a volunteer for the Historical Society of Watertown and Chair of the Watertown Historical Commission.

How often do we take the right to vote for granted? How many elections have we not bothered to vote in because we’re busy or don’t feel we have the time? There was a time, not long ago, when a whole segment of the population was denied the vote simply on the basis of gender. Here’s how the battle for women’s suffrage transpired in Watertown.

As you likely know, the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granted women the right to vote in 1920, however, the initial campaign began here in 1915 when a state constitutional amendment allowing women’s suffrage was proposed. Before the national campaign, the various suffrage campaigns were fought on the state level because, under the U.S. Constitution, individual states defined the franchise.

A little history: a number of states in the west had already granted women the right to vote. Wyoming was the earliest at 1869 and Utah in 1870. However, these were U.S. territories at the time, although when they became states (in 1890 and 1896 respectively), they became the first states to grant the right to vote. In some other states, including Massachusetts, women were allowed to vote in School Committee elections, because of prejudiced beliefs that women were attuned to matters involving children. Not many women availed themselves of this opportunity.

Getting back to the 1915 campaign. The sides in Watertown were fairly well defined: we had both a suffrage movement and an “anti-suffrage” movement. The “anti” group, led by Maria Brigham (the sister of our famous architect, Charles), genuinely believed that women should not have the right to vote. Both groups were substantially composed of women, although the suffragists did have men in the ranks, including those who spoke at public events. Having men among the ranks of the anti’s was probably unpalatable because it would make the men look odious and exclusionary. Interestingly, the local newspaper remained neutral, as leading citizens were on both sides of the issue.

The arguments posited by the suffragists focused on the inferior position of women and how the vote would liberate them and bring them into full membership of society. Inherent in this argument was the prejudiced argument that women would be interested in bettering the conditions of the masses and alleviating suffering, especially among other women and children through their choices at the voting booth. To make their position less threatening to men, they argued that they didn’t wish to do “man’s work” or “usurp his place” in society.

What must have been particularly galling for the suffragists was that women were voting in other states in all races — from the lowest local race all the way up to the election for president. It was simply a matter of geography that prevented their franchise.

The anti-suffragists believed that granting equal voting rights were unnecessary and undesirable on a number of grounds. Some believed that equal voting would interfere with the marital relationship by potentially introducing controversy and division between the partners resulting from different voting patterns. They believed that the franchise would ultimately undermine the home. One pundit remarked, “There are only two ways for a married woman to vote, with or against her husband; and if she votes against him it counteracts his vote, and if she votes with him it duplicates his vote.” A very narrow view, indeed.

Others pointed to the experience of the western states where women could vote. In some instances, very few women actually voted, similar to Watertown’s School Committee elections. At other times, they highlighted when conditions failed to improve for women and children in spite of the effect of women voting. Still others suggested that men had, overall, governed wisely and looked out well for the interests of women. As they saw it, the function of government was maintaining life, public safety and property, all of which depended on law enforcement and the physical power of men to secure them — not women.

As the 1915 campaign season progressed, the battle turned increasingly negative. Instead of focusing on the value of their own position, they began attacking the opposing side and the people involved. This was especially true of the anti’s who attacked the suffragists and their associates as socialists and accused them of undermining traditional Christian values.

All of this jockeying for position and campaigning played out in the local paper, where a dedicated amount of space was given to each side. When it was over, it was clear that the issue had been fully examined in the paper and that the public was fully informed. When the vote was tallied, the amendment failed by almost 2-1 across the state, and by about the same proportion in Watertown.

So, was that it? Would women be destined to remain second class citizens? We, of course, know that the franchise was eventually extended in 1920.

On June 4th of that year, Congress passed the 19th Amendment and it was then sent to the states to determine whether it would be ratified. The process was amazingly fast. Public opinion had shifted markedly in just those few years: Massachusetts passed the amendment on June 25, a mere three weeks later and was the 8th state to do so. The 19th Amendment was passed by Tennessee on August 8th and ratification was complete. The whole process had taken just over two months.

Once ratification was complete, women began to register in Watertown — and in droves. The need was so great that the Town held registration sessions at both the Town Hall and at the East End fire station. Before registration, there were 3,244 men and 694 women registered (remember, women could vote in School Committee elections). It was a presidential election season, so there was lots of attention and interest in voting. As registration progressed, it became almost a competition to see whether there would be more male voters or female voters.

By the time registration ended, there were 8,312 registered voters, although the paper did not report the break-down between men and women. Nonetheless, it did report that for every four new voters, three were women and only one was male. It is very likely that the female electorate was larger than the male electorate in 1920.

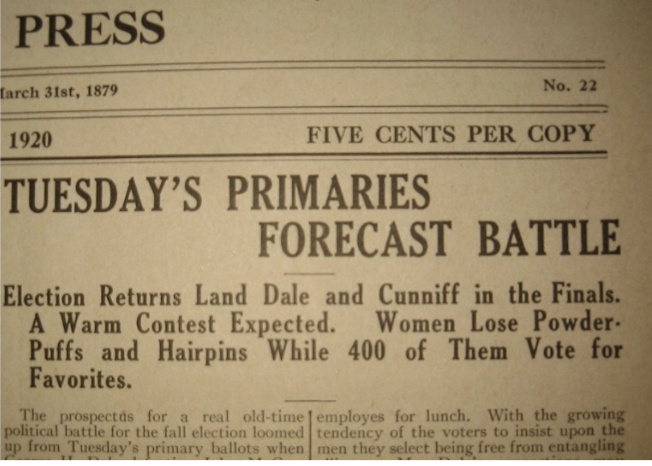

In the presidential election of 1920, 7,744 out of the 8,312 voters exercised their right, a staggering 93%. Poll workers reported that the new female voters took their responsibilities seriously and appeared, in many cases, to be better informed than their male counterparts. They only complained that a number of hairpins and powder puffs were left behind in the voting booth.

Interestingly, among the new registrants was a Mrs. Grace Hale, of 18 Winsor Avenue — one of the leaders in the anti-suffragist movement. Hopefully her experience with voting was a further embrace of her civic responsibilities and participation in public life, and not radical action designed to undermine her family and faith.

David, thanks for this engaging and informative article. It puts history right on our doorstep and we see the women and a few men discussing the merits (with some negativity, as usual when the persuasive arguments dwindle). I love the fact that women had the right to vote for School Committee in Massachusetts and more than 600 registered to vote in Watertown.

And I wonder why the territories were so far ahead in letting women vote–did it have anything to do with the efforts women made in the very survival of the few pioneers so the right to determine how the government behaved became an ungendered necessity? My guess is that they didn’t lose too many powder-puffs at the polls.

Charlie, thanks for making room for some history. Looking forward to more.