By Linda Scott

Watertown Resident

Part 3: Grist for the Mill

So, the Watertown colonists have lots of fish to eat [See Part 2 to read about the fish weir]. What else does any decent English town in the 1600’s need? A grist mill, of course! (If you’d like to see a still functioning grist mill, take a ride out to the Wayside Inn in Sudbury).

In 1634, two years after the weir was installed, a mill dam and millrace were constructed. To run a grist mill, you needed a power source … water. We had water, but it just had to be redirected. Thomas Mayhew had an idea. Let’s build a millrace! (Just a note, there seems to be some dispute on who first owned the mill. Mayhew, a settler named “How” is mentioned (see his land where Mill Creek is), or a miller with one of my favorite last names for his profession, “Thomas Cakebread.” All accounts mention Matthew Craddock as investing in the mill. He lived in England, was part of the Bay Colony business, and was an associate of Mayhew’s.

Watertown had the first millrace built in America to power its grist mill. They called it “Mill Creek.” What is a millrace, you ask? Here’s an excellent video of George Washington’s mill and mill race to show how both the mill and the millrace worked: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FSUu3CvPHr0

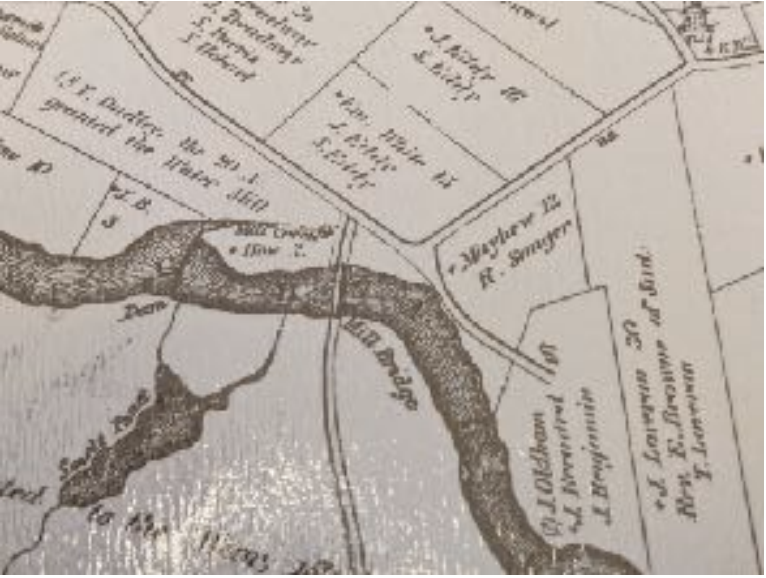

Notice the dam and Mill Creek, the millrace, which turns what is land between the river and the Delta into an island. You can also see the footbridge. This is an area around Pleasant Street and the Delta today.

In a more complete description, S.E. Evans, in his book, Illustrations of the Past says, “Mill Creek, the canal that fed the water flow that powered the mill’s machinery, ran from just above the falls, along Pleasant Street and the south border of Main Street, joined the Treadway Brook (which ran roughly parallel to Spring Street), and re-entered the Charles River just east of the present day Town Dock. The Grist mill and other, later mill buildings were constructed over Mill Creek.”

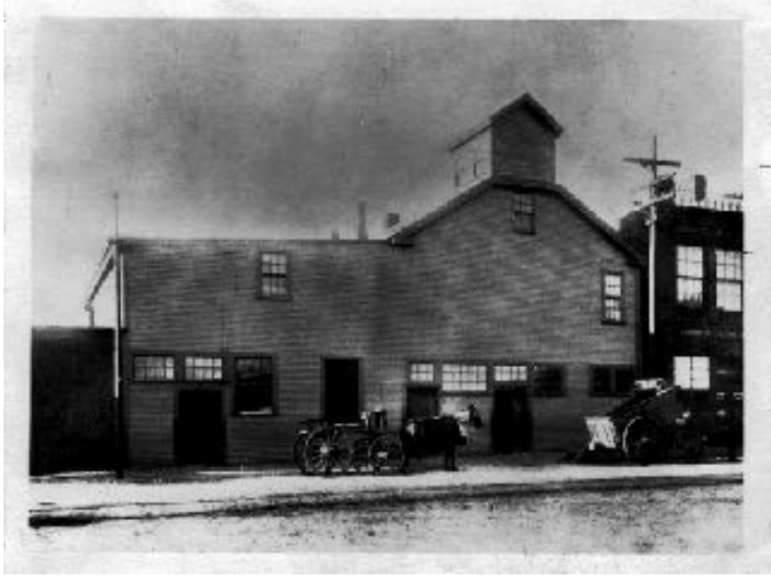

The grist mill was located just below the dam, close to the Charles River until about 1800, when it was moved to Main Street, on the Delta. The old location was replaced by a chocolate factory that eventually moved to Dorchester (Baker Chocolate).

That mill was viewed as so important that it was guarded 24/7 during the King Philip’s War (1675-1676), because it was thought that the easiest way to defeat a town would be to eliminate its ability to grind corn or wheat for food.

Meanwhile, according to Thompson in Divided We Stand, by the fall of 1635, Watertown had some serious problems. They had about 120 immigrants (many family members joining families already in Watertown). They had 54 immigrant families who were just settling there for the winter, ready to move on in the spring. They’d also had a Watertown settler baby boom.

Bad weather, a drought in 1633 and a strong hurricane after that, had made harvests bleak, and they had all of these extra mouths to feed by farmers who weren’t experienced in farming New England soil. To add to their misery, they were short on workers and tools. Some people, including John Oldham, brought food in from other communities to supplement their meager stores.

The environment was so strange to them. William Hammond, an original settler, described it like this: “So many pigeons as might have loaded two or three ships. For two hours we did behold them. They did fly for six miles of breadth, so thick had they covered the air that we did think the first flight was twenty miles afore the last came.” (from Thompson’s Divided We Stand).

There were deadly packs of wolves eating their livestock, except their pigs, which were fast growing, voraciously eating chestnuts and acorns. They loved the climate and were tough enough and big enough to take on the wolves.

The problem was pigs being … well, you know … pigs, could be tremendously destructive to crops. There were fencing ordinances that sprung up from errant livestock destruction of property. It’s said that a pig even grabbed someone’s pillow that was hanging outside to air out and tore it into shreds.

According to Thompson, “Most of Watertown was represented on this roll of dishonor, from the minister and captain of the militia through the deacons and selectmen, down to the lowliest townsman. Despite periodic drives and further regulations as late as 1679 the disorderliness of swine, turned out to forage for themselves, was continuing to cause concern.”

As Watertown got smaller, losing land to other communities like Cambridge, there were far fewer acres of land to divide between settlers, and many people thought that land was being distributed unfairly, creating political turmoil. Times were tough!

Next: Part 4: The Bridges of Watertown Square and Growth on the Delta

Part 4: The Bridges of Watertown Square and Growth on the Delta

Originally, our Watertown Square comprised two squares, Watertown Square and Beacon Square. Beacon Square was where Mt. Auburn and Main Streets met. At that time, Mt. Auburn street stopped at Main Street.

Watertown Square was where Galen Street (where the buses turn around today) and Main Street met. Galen street was on both sides of the river.

From early times, there needed to be a way to cross that river. This was mostly done by ferries, and that could be treacherous! Thomas Mayhew, the same man who built the grist mill and millrace, constructed a rudimentary footbridge across the Charles that connected one side of Galen Street to the other.

In a book with the cringe-worthy title of Thomas Mayhew Patriarch to the Indians, Thomas Mayhew is portrayed as a very rich, landed man who falls victim to the state. He builds this bridge, fully intending to keep it private and collect tolls on it.

The government took seven years to resolve this. In the end, it decided that the bridge should “belong to the Country,” and paid Mayhew with 300 acres of land for this. According to the author, Lloyd C. M. Hare, Mayhew saw this as a great injustice.

By 1643, the bridge was enlarged and strengthened so that one person and one horse could pass over it. Since most things were carried by horseback, that seemed to work, but there was a lot of wear on the bridge.

According to Roger Thompson, the winter of 1666-1667 was especially bad. The base of the bridge was swept away by ice. The town replaced this bridge with 3-foot planks laid across baskets filled with stones.

By 1719, a new bridge was constructed to meet the weight demands of heavy wagons this time. This was built slightly upstream from the old bridge. Since this was the only bridge of this kind around and it was heavily used, it required lots of expensive repairs.

This bridge was called “The Great Bridge of 1719” or “Nonantum Bridge.” To say that this bridge brought great changes to Watertown Square would be an understatement. For years, this was the only bridge across the Charles until you traveled south into Cambridge to Boylston Street/Harvard Square.

Industry and businesses and the workers’ houses that went with them sprung up all around the bridge. It was a great boon to Watertown, bringing business into the community. Three taverns were built nearby, making this a major social center as well. Charles Burke says, this was, however, in contrast to the farming community already settled in Watertown.

We’re well into the 1700’s now, and Burke says, “The real center of the community was developing at the river, below the falls. Here were the mills and stores, and four of the Town’s five taverns. Through here ran the stage coach lines … Heavy goods moved up the river by ship and were unloaded at the Watertown Wharves for wagon transportation inland.” He also says that a postal system was established with a post office near the bridge on Galen Street.

By the time this bridge was 200 years old, it was time for a change! This sorry old bridge is about to be replaced, and with that, great changes were about to occur to the Square itself. One might say that this was the beginning of a series of major reinventions of Watertown Square that are ongoing to this day.

In Part 8, The 1900’s or A Walk in the Park, we’ll look at the newest version of the bridge and the other changes that came with it. Meanwhile, back to the 1700’s.

Next: Part 5: The Roaring 1700’s