The following story is part of a series on local history provided by the Historical Society of Watertown. It was written by Sigrid Reddy Watson Terman for the April 2001 Historical Society newsletter, “The Town Crier”. Sigrid is a former Board member and former President of the Historical Society, as well at a former Director of the Watertown Free Public Library. For several years starting in 1997, she wrote a Watertown history column for the Watertown TAB/Press called “Echoes.”

Sigrid published her columns in a book called “Watertown Echoes: A Look Back at Life in a Massachusetts Town.” The book is available for purchase through the Historical Society of Watertown for $10.00. To purchase it, please contact Joyce at joycekel@aol.com.

[The following account of an interview on August 22, 1957 with John E. Heffernan was recorded by Tom Perry in 1957, and he suggested it might be of interest to people today, many of whom remember John Heffernan, but few if any of whom can recall the period which he describes in such lively fashion. The words in quotation marks are Heffernan’s, and Perry has adhered as much as possible to Heffernan’s actual turn of phrase in the text as he recorded it immediately after the interview took place. He has kindly allowed me to interject editorial comments which may serve to elucidate the text. My comments are in brackets – Sigrid Reddy Watson.]

Bought house today. Agent, a Mr. John E. Heffernan, was in an expansive mood, talked of his youth in Watertown. “This town has no future, but by God it had one hell of a fine past,” he said. He is perhaps 60 years old – not much more, surely – and yet his youth was spent in an era incredibly remote from our own. [Town records indicate that he was born in 1900.]

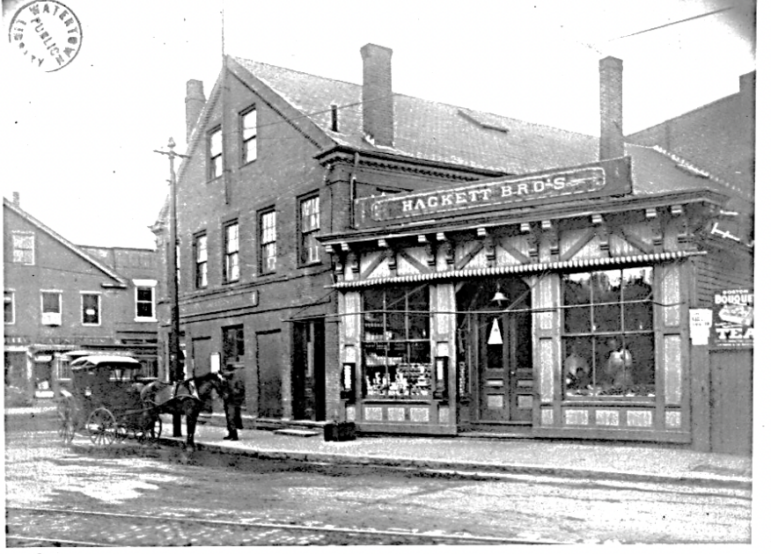

He worked as a boy of 14 – 16 for a grocer named Hackett: a harsh (but fair) old Yankee with a beard. The wage was $1 a day, even though the boss demanded a man’s work from Heffernan. (He was a delivery-boy, and strong for his years.)

Hackett used to fire him often, but always had to hire him back for want of anyone else strong enough to do the work at that wage. Heffernan drove a one-horse delivery wagon. “When you went into the house, you always carried your whip along, stuck down into your boot. Otherwise a passing driver would steal it, and you had to buy your own whips; they cost a quarter apiece.” He, too, was always “on the watch for something to steal” – a pie or cake, perhaps. “They cooked them well, then.”

Watertown had no saloons then, for the “hypocritical puritanical element,” Heffernan said, was strong, and the town was a dry town. [See endnote] Brighton was wet, though, and everyone piled onto the single-track street car – the “Joy Line,” that led to [“One Gentleman’s”] saloon: a “real western-style saloon.” [According to a reliable source, this may or may not be the saloon in question, as the record is obscure on this point. Certainly there was a saloon by that name in Brighton.] “We delivery-boys used to wait in the square to see how many of the town’s ‘worthies’ climbed aboard.”

“The more discreet drank at home, ordering the stuff to be delivered. You could always tell when a keg was delivered, even after dark: a bag of sawdust was thrown down from the wagon as a cushion, and when the keg hit it, there was a unique thud that brought the old ladies to their windows to see who was ordering the stuff.”

Heffernan used to deliver kegs, and always carried a spare “fasset” [faucet] he’d stolen from his father. Thus he and his friends could draw off a bit for themselves. (Once he and a friend tapped the bung [the stopper] too hard; as it went in, it set off a shower of beer inside the covered wagon.) One famous ale – he named it – (also known as “the poor man’s whiskey”) was “so strong that drinking two glasses of the stuff was the same as a trip to the Orient.” The boys often got loaded; he fell off his wagon once, and used to imagine he was driving a four-horse team.

Once four boys, each with a friend and his own horse, met on at 11 or so on a Saturday night and celebrated the end of their week’s labor with a “festival.” The result of this was a “chariot” race coming full-tilt down Mt. Auburn Street from Cambridge way, on the down-hill slope from Walnut Street to Russell Avenue. It ended in a collision with a trolley coming the other way. The poor motorman was winding up his brake to get out of their way, but of course he couldn’t. A horse ran away and a wheel was broken but no one was hurt. The boys’ names were prominently displayed in the local paper the next day. “There was some suspicion,” said the report, “that the boys had been drinking.” “Suspicion!” says Heffernan today!

Heffernan was aware of the hypocrisy of many local dries, for he delivered their beer. One [Protestant] clergyman pretended that the beer was for his stomach ailment. Whenever it was delivered, he’d cry out (for the boy’s benefit), “Amanda, has the doctor’s prescription come yet?” Actually the old boy (the reverend) used to get so drunk he’d catch his cane in the bushes as he passed; “said he had astigmatism, the old liar.” (The minister’s custom was to berate the younger generation every Sunday.)

Watertown then was thinly settled: “a baseball field on every corner.” Cattle were driven through town to Boston on certain days; women kept the wash in, lest strays catch it on their horns and carry it off – a not unknown occurrence. On Mondays it wasn’t a rare sight to see a lady’s wash coming down the main street on a steer’s horns. [The cattle were no doubt being herded to the abattoir across the Charles River in Brighton, which was approximately where Martignetti’s liquor [Editor’s note: now Staples and Party City] store now stands. The odor, and that of the pickle factory, penetrated the neighborhood.]

“Those were the good old days,” said Heffernan, and he seemed to mean it.

Once when he was making a delivery to the Dyers’, their dog, Flossie, chewed up his wrist. (He hadn’t seen her sleeping in the dark hall.) Flossie attached him, but he got out his whip. And just as he was laying into her with a ready will Mr. Dyer came in and gave him a stiff lecture. Heffernan went back to Hackett’s after his rounds and was called in to see “old Whiskers” [Hackett].

“ ‘You’re fired, Heffernan, Dyer says you attacked his dog.’ “

“So I showed him my wrist which Flossie had chewed up pretty good and Hackett gets on the phone and calls Dyer.

“ ‘Dyer, you’re a bloody liar. You said my delivery boy assaulted your dog without reason. He should have attacked her and if he had any sense he should have left her dead. You’re a damned

liar, and your dog bit my delivery boy. If you’re not careful you’ll have a libel suit on your hands You’re none too prompt about paying your bills, and to hell with you,’ and he slams down the

phone.

“So he gave me three dollars to go to the doctor which I put in my pocket. The druggist bound it free, and it healed by itself: ‘Christian Science!’ I treated myself, you see, and had old Frank on the corner tape it which he did for free. [Some sources suggest that the drug store may have been Butler’s, which stood on Main Street near the corner of Merchant’s Row.] I felt entitled to the money after working so long for Hackett doing man’s work for a boy’s pay. Old Hackett was hard, but fair.”

For entertainment: “Do it yourself” – weddings, christenings. The delivery-boy could tell the best affairs to crash by watching the liquor deliveries.

[Endnote: at this time, Prohibition was a town-by-town local ordinance. The Temperance Movement gained strength during the 19th century, supported by the W.C.T.U, certain religious denominations (e.g. the Baptists and Methodists), and local arbiters of morals; this preceded the passage of a Constitutional amendment, and the passage, in 1919, of the Volstead Act, an attempt to enforce nation-wide prohibition of the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcoholic beverages. After Repeal of the 18th Amendment by the passage in 1933 of the 21st , some states passed their own prohibition laws on a state-by-state basis; this practice has continued until fairly recently. Some Watertown residents with long memories perceive an irony in the present location of a liquor store a the corner of Mt. Auburn Street and Baptist Walk, the former location of the Baptist church.]

— Recollection of conversation with John Heffernan by Thomas W. Perry, 64 Russell Avenue, Watertown; used by permission. Transcribed by Sigrid Reddy Watson from original manuscript, January 2001.

Very enjoyable story from our town history! I remember by brother delivering groceries in a hand cart. Also WWI Veterans with amputated limbs sitting outside of a bar at the Delta with cups, selling pencils, as my brother set up his shoe-shine box, and on Saturday mornings observing them on the grass sloping down from the Unitarian Church toward the then Gray’s Landing, where among other businesses, was the Railway Express entity, and the coal depot. This story brought back old memories of the rail road track that ran along the brook alongside Saltonstall Park toward Waltham and the Quincy Cold Storage.