This article is part of a series on local history provided by the Historical Society of Watertown. It was written by Joyce Kelly, Board member of the Historical Society of Watertown. Joyce writes articles for the newsletter and is the newsletter editor. This was published in our October 2007 newsletter, “The Town Crier.”

As we reported in the January 2005 issue of The Town Crier, the Historical Society of Watertown has been granted a $500,000 award from the state for the Edmund Fowle House, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. In July 2006 we received a grant of $200,000 from the Massachusetts Office of Travel & Tourism., also for the Edmund Fowle House. The Executive Council of the Provincial Congress met in a room on the 2 nd floor of the Edmund Fowle House during the first year and a half of the Revolutionary War in 1775 and 1776. The Executive Council, also known as the Governor’s Council, acted in place of the Governor and Lieutenant Governor from July 20, 1775 until the adoption of the Constitution in 1780.

Also, the Treaty of Watertown was signed in this house on July 19, 1776, a mere 15 days after the signing of the Declaration of Independence. This first international treaty, between the newly formed United States of America and the MikMaq and St. John’s tribes of Native Americans in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, was a treaty of alliance and friendship but it also secured our

northern border.

Both of these grants were received largely through the efforts of Senator Steven Tolman, a staunch supporter and advocate of historical sites in his districts.

The Historical Society has always known that the Fowle House belonged to Edmund Fowle II during the Revolutionary War. For years, we thought that this house originally belonged to Edmund Fowle I, the father, and was passed down to Edmund Fowle II, the son. We now know that is not the case.

As we reported in our January 2007 newsletter, our dendrochronology study revealed that the trees to build this house were felled in the winter of 1771 – 1772, and the house was built in the

spring of 1772.

Edmund Fowle II was born on December 31, 1747. He was the first son born to Edmund Fowle I and Abigail Whitney. Edmund II had an older sister, 3 younger sisters and 4 younger brothers.

His father, Edmund Fowle I was a cordwainer, meaning he worked with leather and made shoes. His shop was on the south side of the Charles River near the present Galen Street. An entry

from the Town Records of January 10, 1742 shows that encroachment on public land was a problem even back then. The record states, “Where as Sundry persons have Errected new fences where by they have taken in part of ye Publick ways & Town ways as also Some buildings Errected on ye publick ways … Edmund Fowl be Notifyed to remove their Shops from of ye High way.”

Edmund Fowle I, the cordwainer, died in 1771, before the present Edmund Fowle House was built. His business must have been very lucrative for his widow and children were well provided for in his will, especially his son Edmund II, who received “double portions out of my Real Estate and my sons John, Jeremiah and Samuel each have a single share and my daughters to have but one half so much …”

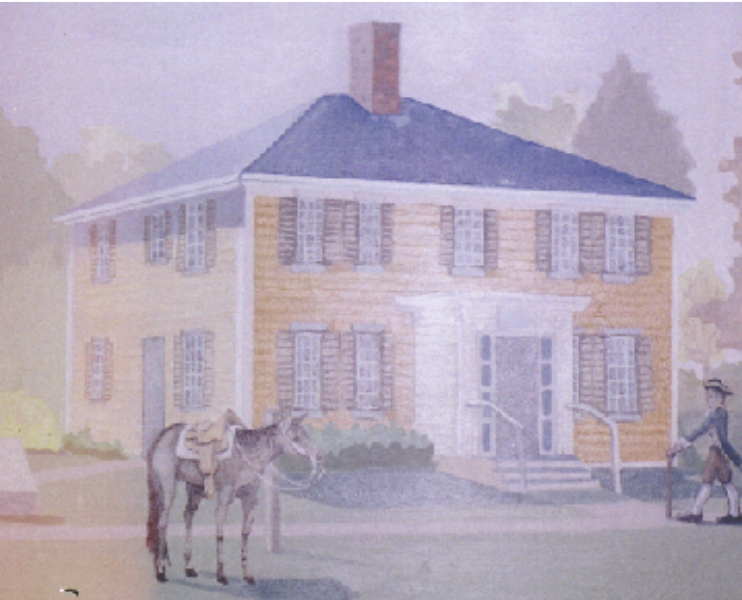

Perhaps this large inheritance is why Edmund Fowle II was able to build such a fine house for himself and his bride, Mary Cook, who he married on November 17, 1772, the same year the house was built. Edmund Fowle’s house, now owned by the Historical Society of Watertown, was built on the site where Mt. Auburn Street joins Marshall Street. Marshall Street did not exist at that time. It was a very fine house, two-and-a-half stories high (many houses of this period were only one story high) with inside front and back staircases to the second floor and six fireplaces – three on each floor. At least one of these fireplaces had a slate hearth instead of a brick hearth – a sign of prosperity. This discovery was made recently by our Architectural Conservator, Andy Ladygo, who uncovered a sloped impression in front of the parlor fireplace that most likely held a large piece of slate as opposed to an array of bricks that would fit in this indentation.

Edmund II’s first child, Edmund, was born July 29, 1774. His wife, Mary, died around this time, perhaps in childbirth. Edmund did not marry again until about 1784. He would not have raised this child alone. Edmund’s mother probably took baby Edmund and raised him, as she still had three children of her own under 18 years old (Edmund II’s siblings) and lived in a house on the Fowle property. This would have left Edmund II living in his house alone.

Less than a year later, the battles in Lexington and Concord occurred, marking the beginning of the Revolutionary War. On that day a company of Watertown men, led by Capt. Samuel Barnard, marched toward Lexington and encountered Lord Percy’s retreating army. They followed and harassed the British forces. Town Records show that 28 year old Edmund Fowle was on the muster roll of this company that served during the Lexington Alarm on April 19, 1775. Edmund’s 19 year old brother, John Fowle, is also on the muster roll.

On April 22, 1775, three days after the battles in Lexington and Concord, the Provincial Congress adjourned to the Watertown Meetinghouse, located in the Common Street Cemetery. (Today, four granite posts with plaques mark the four corners of the meetinghouse that stood there from 1754 to 1837.) Military preparations dominated their working hours. Many new Committees were formed to help with these preparations and met in houses nearby, including Edmund Fowle’s which was located very close to the Meetinghouse.

On July 20, 1775, the Provincial Congress elected a 28-member Executive Council, or Governor’s Council, to serve as its upper house and as its executive body without a governor. These two bodies proceeded to govern the Province of Massachusetts Bay until the adoption of the State

Constitution in 1780.

Though built in the spring of 1772, the second floor of Edmund’s house had not been completed by the spring of 1775. Perhaps the death of his wife relegated this task to the back burner. In any case, the manuscript written by Maud Hodges that later became “Crossroads on the Charles” describes the second floor of the Edmund Fowle House as being “one big open space” in 1775. A July 22, 1775 entry in the Journals of the House of Representatives states “The Committee appointed to provide some convenient Place for the Council to sit in; reported, verbally, That a large Chamber in the House of Mr. Fowle’s might be procured; but being unfinished, the Committee recommended that there be a rough Floor laid, and Chairs provided for that Purpose. The Report was accepted, and Capt. Brown, Capt. Dix, and Major Fuller, were appointed to prepare said Chamber accordingly.”

Work began on outfitting the second floor of Edmund Fowle II’s house to accommodate meetings of the Executive Council. We are not sure if Edmund was staying at the house while the Council met, or if he found accommodations elsewhere. Provincial Congress President James Warren wrote to John Adams from here on October 20, 1775 saying, “… the crowd of company here, must be my excuse. Every body either eats, drinks or sleeps in this house, and very many do all, …” In any case, Edmund does not disappear from the documentation of the time.

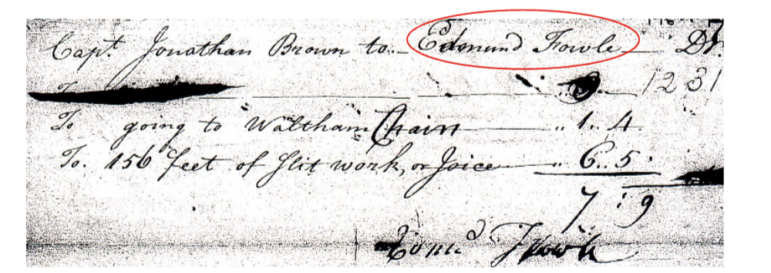

The Massachusetts Archives on Morrissey Blvd. in Dorchester has an incredible collection of colonial and Revolutionary War Era records. These resources are available to the public for research. Historical Society Council members Joyce Kelly, Pam Pinsky and Marilynne Roach spent several days there earlier this year and found many invoices pertaining to Edmund Fowle, the Council Chamber, and the goings-on in Watertown in 1775 and 1776.

An invoice from December 1775 found in the Mass. Archives shows that Edmund Fowle submitted requests for payment for going to Waltham for chairs and for 156 feet of his work on “joice” (joists) “by order of the Committee for fixing the Council Chamber”. In another invoice from that month Edmund is being paid for “going Down to Cambridge…to get a Man to alter the Stoves in the Meeting House” and “Carrying a Letter down to General Washington”.

An invoice from October 1775 says, “To Edmund Fowle Bill for Dinners … passed by the Committee for … preparing the entertainment for the gentlemen from ye Several Colonies.” Minutes from the House of Representatives Journals show that Edmund petitioned for “Consideration and Allowance for the Use of his House since April last, for Committees of the Court and of the Congress, and for the Office of the Clerk of the House.” This shows that Committees were meeting in Edmund’s house before the 2nd floor Council Chamber was even outfitted. Obviously, they were meeting downstairs.

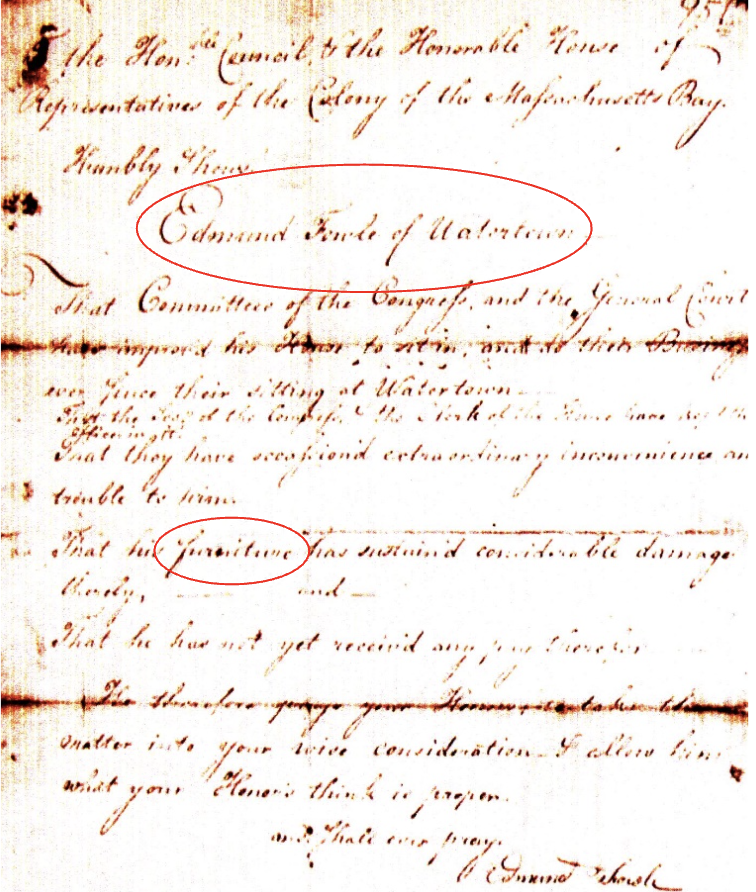

Another invoice from 1775 says, “to the Honorable Council and the Honorable House of Representative of the Colony of the Massachusetts By Humbly Shows Edmund Fowle of Watertown – That the Committee of the Congress, and the General Court have improved his House to sit in, and do their Business ever since their Sitting At Watertown – That the Secy of the Congress & the Clerk of the House have kept their office in it That they have occassioned extraordinary inconvenience and trouble to him That his furniture has sustained considerable

damage … That he has not yet received any pay,,,”. A document from January 1776 states, “In House of Representatives propose that there be paid out of the Treasury of this Colony to Edmund Fowle the Sum of four Pounds ten shillings for the Extraordinary Trouble that Committee have (can’t decipher) in sitting in his House from the first day of the Congress sitting & for Burning of Wood & Candles…and for the damage done his Furniture”.

Many thanks go to Marilynne Roach who transcribed these invoices and is in the process of transcribing the minutes of the Executive Council.

Watertown records show that in March 1776 the Watertown Milita marched, by order of General Washington, to reinforce the army in taking possession of Dorchester Heights. This company was in service for five days and 29-year-old Edmund Fowle was one of the men who was paid for their service during the evacuation of Boston.

Town Records show that from 1778 to 1783 payments were made to many soldiers for service and for ‘the benefit of the present War.” Edmund Fowle’s name shows up as being paid in many of these records, including one “to Reinforce the Guards at Cambridge” who were guarding prisoners.

Edmund is referenced in the Town Records in the late 1770s as a Warden and a Tythingman. He seems to have been very much a part of what was going on in Watertown during the Revolution.

Edmund married Huldah Curtis in 1784. His next child, born in 1785, was named “Moses Gill Fowle” after one of the 28 member Council. Moses Gill was not a local resident. He lived in Worcester County. He and Edmund must have become very good friends during the 1775-1776 period. Edmund had seven more children with Huldah. He named his sons after other prominent men in town at the time, such as Marshall Spring Fowle (a prominent Watertown doctor), Stephen Cook Fowle (of the Watertown family that housed Paul Revere for nine months during the War) and William Hunt Fowle (Watertown Lawyer and Justice of the Peace).

During the 1780s and 1790s, Edmund served Watertown in many capacities, including Surveyor of Highways, Constable, Fence Viewer and Collector of Taxes. He was a Watertown Selectman in 1795 and 1804-1807. A court case in 1799 lists Edmund II as a “Yeoman” (an independent farmer).

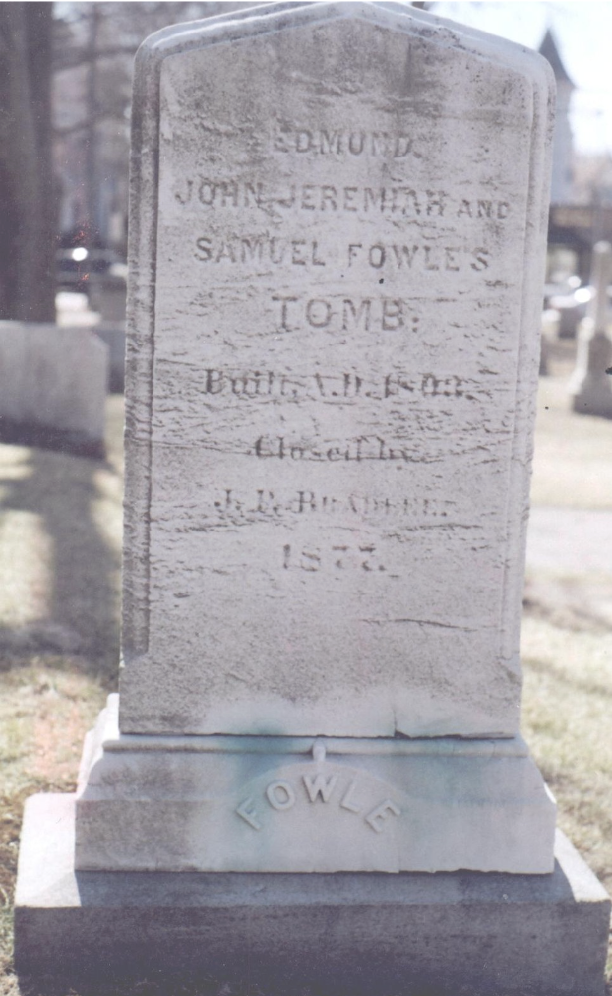

Edmund Fowle II died in 1821. His tomb is in the Common Street Cemetery. The stone on top of the tomb reads:

EDMUND,

JOHN, JEREMIAH AND

SAMUEL FOWLE’S

TOMB

Built A.D. 1803

Closed in

J.P. Bradlee

1877.

(John, Jeremiah and Samuel are Edmund II’s brothers. Joseph P. Bradlee was married to Edmund’s daughter Rebecca.) Knowing that Capt. John Fowle is buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery, your editor wondered who might have been buried in this tomb in his place. A trip to Watertown’s Dept. of Public Works (DPW) to see the burial record for this tomb was of no help. Usually, the burial record will give information such as the date the lot was purchased, the owner, a listing of those buried in the lot, death dates, age at death, and often a map of how the bodies are situated in the lot. Unfortunately, the DPW record for this tomb is blank, as many are from that early period of time.

One side note of interest – Edmund II’s brother, Ebenezer Smith Fowle, was not left shares of Edmund I’s real estate, as the other sons were. Edmund I’s will states specifically that he is “to have no part thereof.” He also is not named on this tomb, as all the other sons are. I wonder why … this may be a story for a later newsletter!